Arizona. The Cold War in Tucson: Touring a Titan II Missile Silo

Growing up in the 1960s and 70s, I remember school “duck and cover” drills that heightened anxiety about Russian missiles and nuclear Armageddon. Although fading as U.S.-Soviet relations began to thaw, the exercises left a deep impression on young Americans about the dangers of another global war. A few years ago, I became aware that a former Cold War missile silo near Tucson, Arizona was open to the public. Some historical background may be useful as a prelude to describing my visit to a Titan II Missile silo. During the early 1960s, the U.S. Air Force constructed a complex of eighteen underground missile silos forty kilometers south of Tucson. Becoming operational in December 1962, the facility’s Titan II ballistic missiles had a range of 8,800 kilometers and traveled at speeds of up to 25,700 kilometers an hour. With a thirty minute flight time, the Titan II was the largest (31.4 meters) and heaviest (149,700 kilograms) nuclear missile ever built by the U.S. It was also the first Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) capable of being launched from a hardened underground facility.

Titan II missiles were built in support of a U.S. military doctrine called “Mutual Assured Destruction” (MAD) that speculated that an enemy such as the USSR would be reluctant to launch a first missile strike knowing that the U.S. would respond with an equally devastating counterstrike. Hoping that their weapons would never be used, the motto of Titan II crews was “peace through deterrence.” Between the mid-1960s and their decommissioning in the late-1980s, forty-four Titan II missiles were deployed in Arizona, Arkansas, and Kansas.

Titan II underground silos were spaced thirteen to nineteen kilometers apart and reinforced to withstand a nuclear attack. Individual silos were staffed twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, and 365 days a year by a four-person crew of two officers and two enlisted technicians. Crews worked four-day rotations and were considered “on alert” for their first and last 14-hour shifts. An order to launch could only be initiated by the U.S. President by sending a thirty-five-letter code. After receiving and entering the code, two keys in the missile control room had to be turned within two seconds of each other. The key slots were located on opposite sides of the room so that both launch officers had to turn their keys simultaneously. A launch would commence within sixty seconds of a verified launch order, a significant improvement over the earlier Titan I missiles that had a fifteen-minute launch preparation time. On reaching its target, the missile would create a nine-megaton blast and fireball that was lethal to anyone within a thirty-two kilometer radius. The missile’s guidance system was accurate to within nine hundred meters. Fortunately, no Titan II missile was ever fired in anger.

Decommissioned in 1984, Site 571-7, was formerly part of the 390th Strategic Missile Wing, headquartered at nearby Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Tucson. Today, the site is managed by a non-profit organization called the Arizona Aerospace Foundation. The silo facility and missile museum are located in Sahuarita, just off U.S. Interstate 10. We drove to the facility and parked near the small visitor center. From a distance, the fenced-in facility would not have attracted much attention. We paid the modest tour fee and browsed interpretive displays as we waited for our assigned time. The 45-minute tour began at the museum. Walking outside, we passed a fueling trailer and a missile engine display before entering the underground bunker.

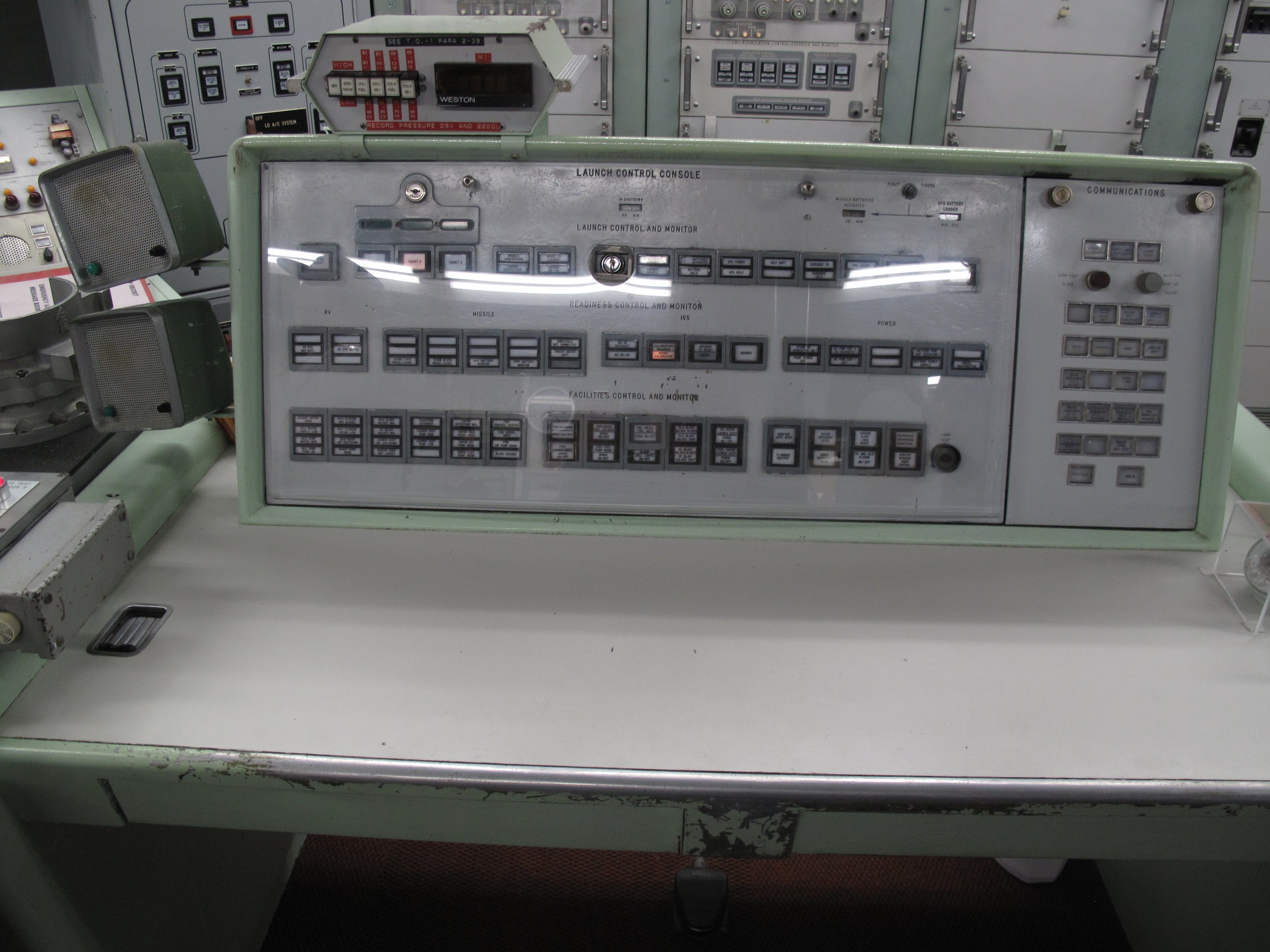

Adjacent to the bunker’s entrance was a massive concrete dome that could be moved to cover the top of the silo during an attack. We walked through the entrance and down a staircase. In the event that the staircase or entrance portal was damaged or destroyed, the missile crew could exit through an emergency hatch located at the end of a three-meter tunnel that was connected to an airshaft. The launch facility is on three levels. Our guide explained that the vertical shaft around the missile, called the launch duct, has service platforms at each of eight levels. A concrete wedge at the bottom of the launch duct is known as the flame deflector. During a launch, flames would be diverted by the deflector into two ducts that extended to the surface. Continuing downward, we passed through a long corridor filled with electrical conduit that led to two large blast doors. Passing the crew’s quarters, we entered the launch center where our guide explained how codes were decoded and confirmed. Dual safes with combination locks contained launch keys and target information. After finding volunteers to sit at the control console, our guide explained how a launch was initiated. Subsequently, we walked through a corridor filled with cables to a platform where we could see a decommissioned Titan II missile sitting upright in the silo. I tried not to think about what would have happened if this missile had been used against an unsuspecting city or other populated target. When the tour ended, we returned to the upper level for additional time in the museum

Titan missiles were also used for non-military missions including launching Earth-orbiting satellites and transporting Gemini capsules into space. Today, a few Titan II silos are located on private property near Tucson including one that recently sold for $500,000. Titan IIs are no longer used by the U.S. military. The current U.S. Air Force ICBM is the Minuteman III Missile. About four hundred Minuteman IIIs are presently deployed in Wyoming, Montana, and North Dakota.